Overview

Climate change is increasing the risk affordable multifamily housing faces from natural hazards. These events pose significant challenges to developing safe and affordable communities. Hazards of particular concern to the state of Colorado are hail, wind, wildfire, flooding, drought, and extreme temperature swings. For a deeper dive into state hazards, consult the 2023 Colorado Enhanced State Hazard Mitigation Plan.

Hail and Wind Storms

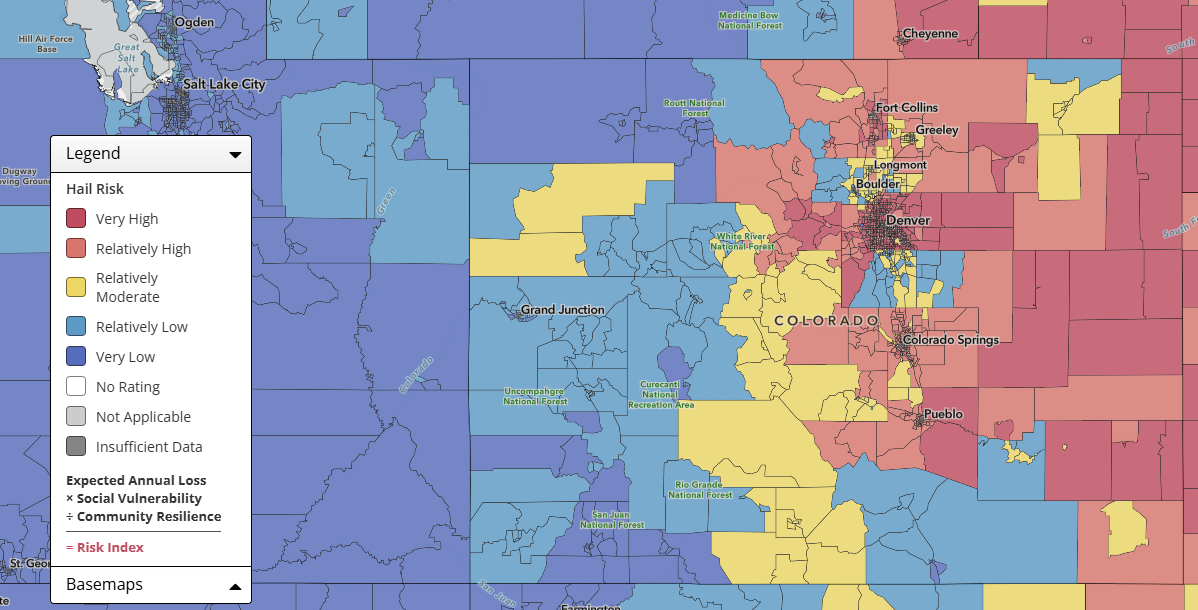

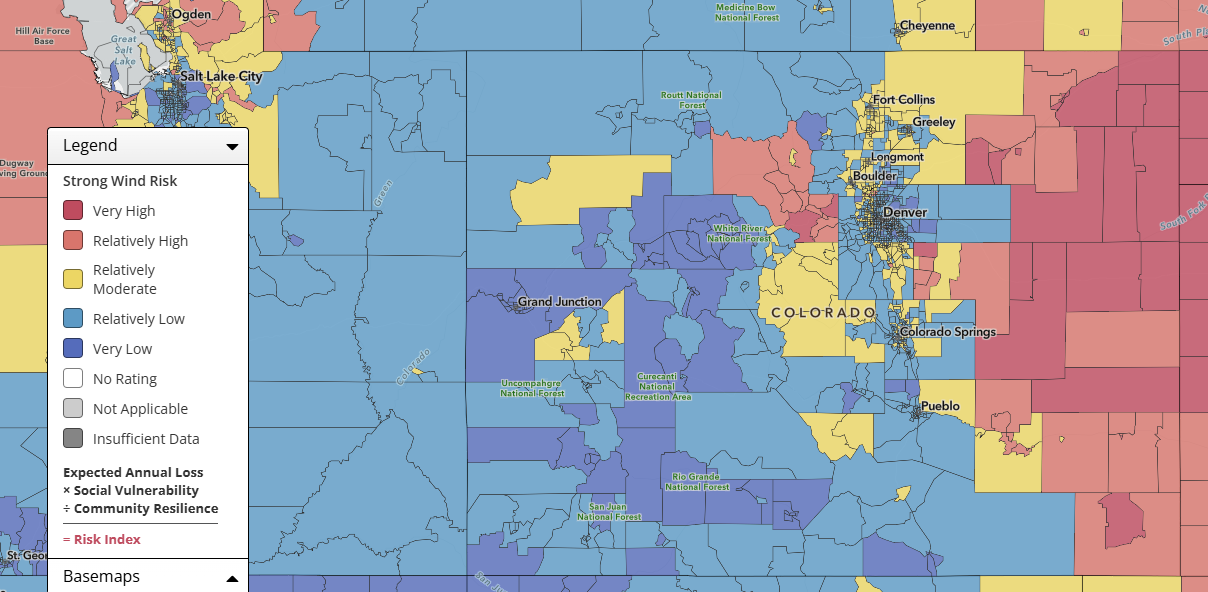

Hailstorms and high winds are some of the most frequent and destructive weather events in Colorado, causing billions of dollars in damage annually. Between 1980 and 2024, Colorado experienced 42 severe storm events, with estimated total damages ranging from $20 billion to $50 billion according to the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). Affordable multifamily housing developments without the resources to invest in resilient building systems are especially vulnerable.

Geographic Context

-

High Plains and Front Range areas are high risk areas for wind and hail.

FEMA National Risk Index - Hail Risk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). FEMA National Risk Index Data v 1.19.0 [Dataset]. Department of Homeland Security. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/data-resources. Explore the Hazards Map at https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map.

FEMA National Risk Index - High Wind Risk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). FEMA National Risk Index Data v 1.19.0 [Dataset]. Department of Homeland Security. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/data-resources. Explore the Hazards Map at https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map.

Vulnerable Building Systems

-

Roofing: Roofing systems are susceptible to hail damage, particularly when constructed with non-impact-resistant materials.

-

Windows and Skylights: High wind and hail can shatter unprotected glass, leading to water intrusion and costly repairs.

-

HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning): Condenser coils and fins are easily dented by hailstones, reducing air flow and heat exchange efficiency. Fan assemblies can become misaligned and electrical components damaged.

-

Siding and Cladding: Hail can dent or crack siding, leading to water infiltration and structural damage.

Key Challenges

-

High Winds: High winds may increase the risks described above by dislodging roofing and siding materials.

-

High Repair Costs: The Colorado insurance industry is shifting its approach to hail policy deductibles, transitioning from flat-rates to five percent of the total property value. The replacement costs to multifamily building owners for roofs, windows, and HVAC systems after hail damage can be prohibitively expensive under these new policies.

-

Design Limitations: Flat roofs or inadequate roof slopes can exacerbate hail-related drainage issues. Poorly performing water management systems, such as clogged gutters, can amplify damage.

-

Insurance Limitations: Increasing insurance premiums or high deductibles for hail-prone areas create financial strain for building owners. Some insurance providers may limit or exclude hail coverage in high-risk regions with frequent claim events.

Wildfires

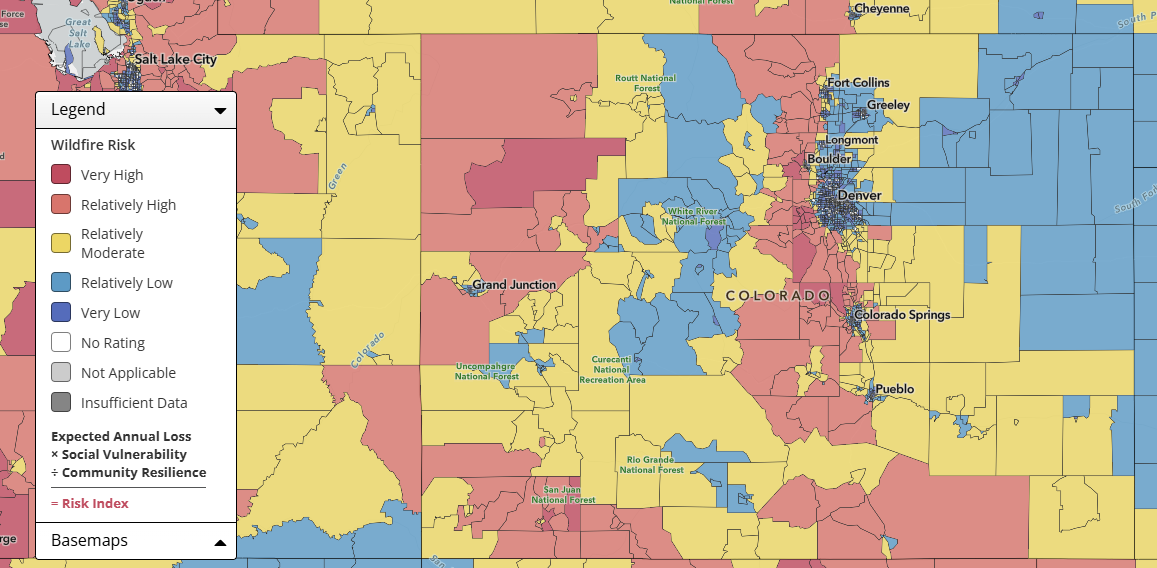

Colorado’s wildfire season impact is increasing due to a combination of drought, rising temperatures, and real estate development in fire-prone areas. As a result, the state faces escalating challenges including reduced air quality, structural fire damage, and insurance liability. The state experienced nine multimillion dollar wildfire insured loss events between 2002 and 2021, with the Marshall fire loss exceeding $2 billion (RMMIA, NCEI, NOAA).

Geographical Context

-

Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) regions are particularly vulnerable to wildfires. Areas at risk of wildfires in Colorado include the Front Range Foothills and mountain areas.

FEMA National Risk Index - Wildfire Risk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). FEMA National Risk Index Data v 1.19.0 [Dataset]. Department of Homeland Security. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/data-resources. Explore the Hazards Map at https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map.

Vulnerable Building Systems

-

Roofing: Roofs constructed from combustible materials, such as wood shingles, are vulnerable to ignition from wind-driven embers during wildfires. Although the use of wood shingles has been prohibited in several Colorado jurisdictions for new construction, many existing homes and commercial buildings still utilize this flammable roofing material.

-

Siding and Cladding: Materials like vinyl can melt or ignite when exposed to heat or flames.

-

Windows: Single-pane windows can shatter under intense heat, allowing flames and embers to enter the building.

-

Vents and Soffits: Unprotected openings can allow embers to enter attics and crawl spaces, leading to internal ignition.

-

HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning): Air intakes can pull in embers and smoke, compromising indoor air quality and potentially igniting internal components. In addition, outdoor HVAC units are at risk of damage from radiant heat or direct flames. Inadequate filtration can allow wildfire particulate matter to enter apartments through ventilation systems, posing health risks to residents.

-

Structural Design: Shared walls and floors in multifamily units can propagate fire and smoke across multiple residences. Overhangs, balconies, and other protrusions can trap heat and increase fire spread.

-

Landscaping and Surroundings: Vegetation close to the building can act as a ladder fuel, allowing fires to climb from the ground to the structure. Wooden decks, fences, and attached structures can quickly ignite and spread flames to the main building.

Key Challenges

-

Mitigating Ember Intrusion: Protecting vents, soffits, and windows with ember-resistant materials or screens is often overlooked in multifamily buildings.

-

Regulatory Barriers: Codes and standards for wildfire resilience, such as those in the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC), are not consistently adopted across jurisdictions in Colorado’s Wildland-Urban Interface areas.

-

Shared Infrastructure: Damage to utilities such as power and water systems can exacerbate recovery efforts in multifamily buildings.

-

Insurance Limitations: Rising premiums, limited coverage availability, and nonrenewal rates in high-risk areas can impose significant financial burden on property owners and developers.

Flooding

Colorado's topography, marked by steep mountain terrain, rapid snowmelt, and intense summer thunderstorms, makes portions of the state susceptible to flooding. In mountain regions, flash floods are a frequent hazard as steep slopes funnel water into narrow valleys, quickly overwhelming waterways and threatening nearby developments. Areas impacted by wildfire burn scars experience heightened soil instability, increasing the dangers of flash floods. Urban and suburban areas face their own challenges. Impervious surfaces and overburdened drainage systems can cause micro-flooding. Climate change is expected to intensify these risks, bringing more frequent and severe rainfall events concentrated over shorter periods.

Geographical Context

-

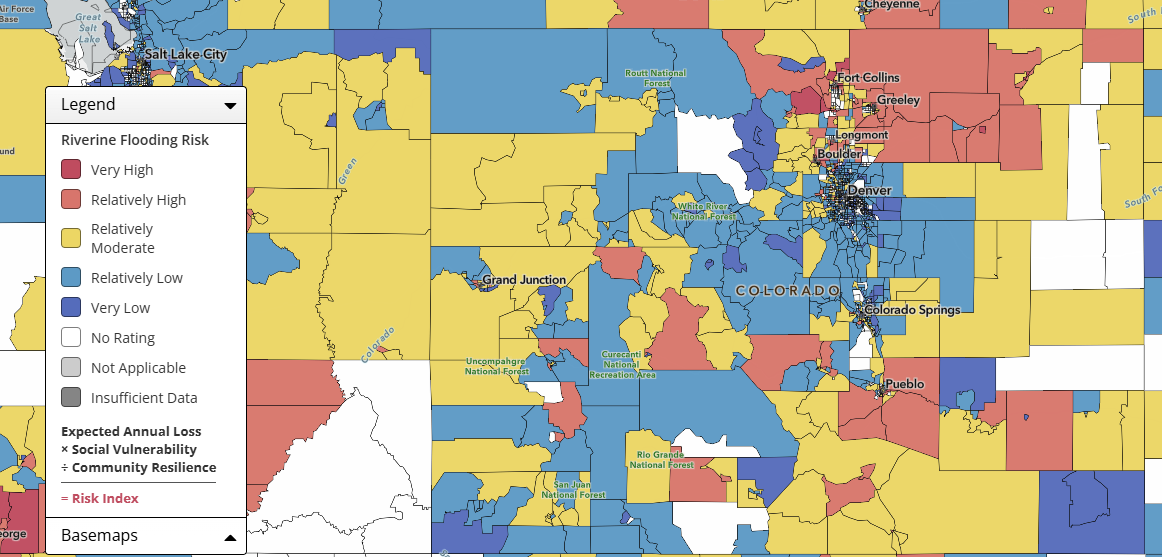

Front Range and Urban Corridors: Some areas within the front range face flood risks due to proximity to major rivers (e.g., South Platte River) and limited drainage in urbanized zones.

-

Mountainous Areas: Steep slopes in the Rockies lead to rapid water accumulation during storms, creating dangerous flash floods in valleys and canyons.

-

Eastern Plains: While less common, flooding on the plains can occur from prolonged heavy rainfall or river overflow.

FEMA National Risk Index - Flooding Risk

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2023). FEMA National Risk Index Data v 1.19.0 [Dataset]. Department of Homeland Security. https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/data-resources. Explore the Hazards Map at https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/map.

Vulnerable Building Systems

-

Building Foundations and Lower Levels: Basements and ground floors are prone to flooding, leading to structural instability, water damage, and mold growth. Prolonged saturation of soil around foundations can cause settling, cracking, or collapse.

-

Parking Structures: Underground or ground-level parking garages can become inundated, damaging vehicles, electrical systems, and storage spaces. Lack of proper drainage systems contributes to water accumulation.

-

Shared Utilities and Mechanical Systems: Centralized HVAC, electrical, and water systems located in basements or lower levels are at risk of damage, leading to system-wide outages for all units. Elevator shafts are particularly vulnerable to water intrusion, which may lead to costly repairs and render elevators inoperable.

-

Building Envelope: Poorly sealed doors, windows, and siding allow water intrusion, leading to interior damage. Roof drainage systems, such as gutters and downspouts, can fail or become overwhelmed, contributing to interior leaks.

-

Ingress/Egress Points: Flooding of shared entrances, stairwells, and hallways impedes evacuation and emergency response. Accumulation of debris can block emergency exits, compounding safety risks.

-

Shared Outdoor Spaces: Floodwaters can damage playgrounds, communal green spaces, and recreational facilities, reducing usability and increasing repair costs. Impermeable paving around multifamily structures increases runoff, worsening localized flooding.

Key Challenges

-

Design Limitations: Older multifamily buildings often lack flood-resistant design features, such as elevated structures, flood-proof materials, or effective drainage systems. Retrofitting existing structures to meet modern flood resilience standards is costly and logistically challenging.

-

Insurance Challenges: Multifamily property owners face expensive flood insurance premiums or limited availability in high-risk zones, particularly for buildings without prior mitigation measures.

-

Emergency Access: Flooding can obstruct roadways and access points to multifamily complexes, delaying emergency response and evacuation efforts.

-

Recovery Logistics: Coordinating repairs across numerous units and central systems can lead to extended recovery timelines, leaving residents without essential services. In addition, mold remediation and structural repairs are more complex and costly in multifamily settings due to the interconnected nature of units and shared spaces.

Drought

Colorado is at risk of drought due to a semi-arid climate and reliance on snowpack for water supply. Rising temperatures and earlier spring melt-offs are increasing this risk. Drought conditions not only threaten water availability, but also exacerbate wildfire conditions, strain aging infrastructure, and amplify the urban heat island effect (when cities experience higher temperatures due to heat absorption from pavement and buildings).

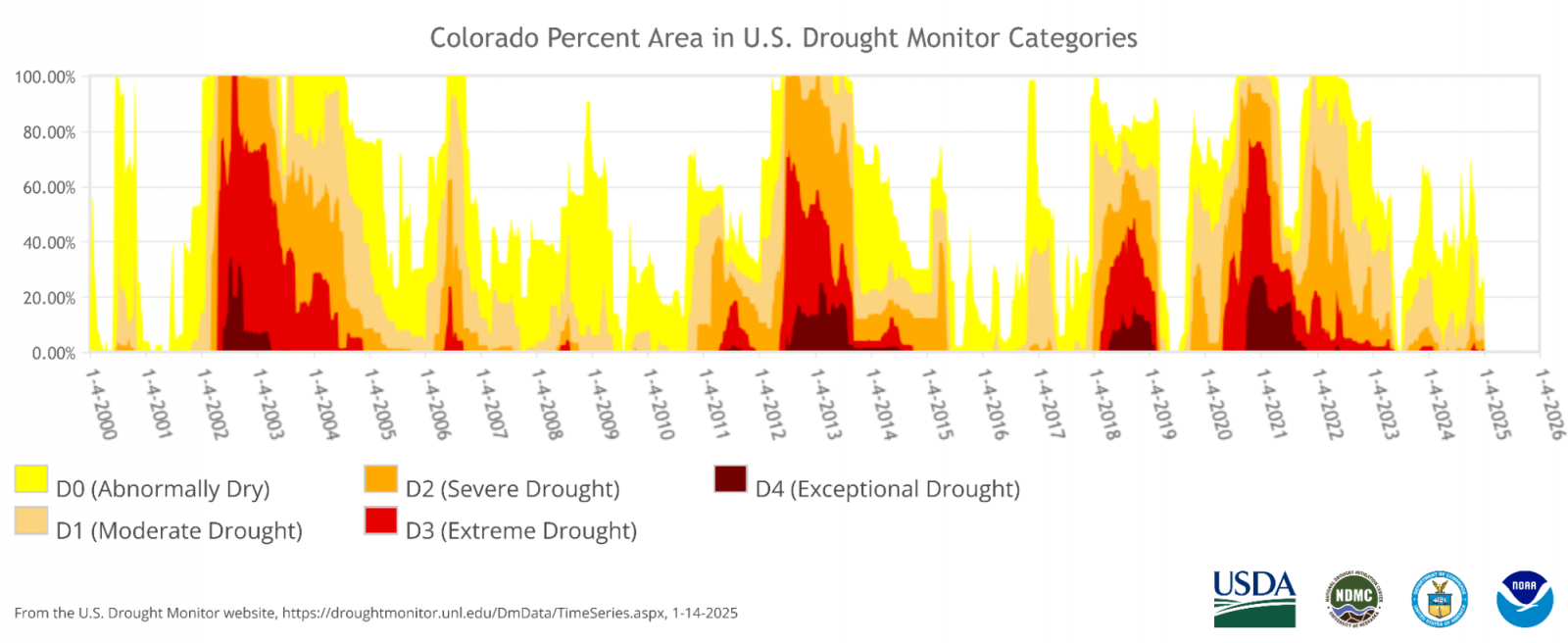

Drought has had a substantial economic and environmental impact on Colorado. Sixteen of the 76 confirmed billion-dollar hazards recorded in the state between 1980 and 2024 were drought related, with damages totaling between $5 billion and $10 billion (based on CPI-adjusted estimates). As climate risks continue to evolve, drought frequency and severity are projected to increase. Rising temperatures are expected to drive higher evaporation rates, resulting in drier soils. Additionally, less snowpack and earlier snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains are anticipated to reduce spring and summer runoff, stressing water supply in the Western Colorado River Basin.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is jointly produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the United States Department of Agriculture, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Map courtesy of NDMC.

Geographical Context

-

Western Colorado River Basin: Dependence on snowpack for water supply, with reduced spring runoff due to earlier melting periods.

-

Eastern Plains: Vulnerability to prolonged dry spells that impact local water resources.

-

Urbanized Areas Along the Front Range: Water supply stress from population growth and increasing demand.

Vulnerable Building Systems

-

Potable Water Distribution: Older plumbing systems are more prone to leaks and have higher flow rates compared to newer fixtures, increasing water consumption.

-

Irrigation: Outdated or poorly maintained irrigation systems contribute to water waste.

Key Challenges

-

Infrastructure Stress: Aging water infrastructure is more prone to leaks and failures, complicating drought response efforts.

-

Heat Intensification: Drought exacerbates the urban heat island effect, increasing cooling needs and energy demand in multifamily housing.

-

Resource Scarcity: Drought conditions reduce the availability of potable water, increasing competition for limited resources.

-

Economic Impacts: Rising utility costs and increased reliance on imported water supplies create financial burdens for low-income residents.

-

Wildfire Risk: Extended drought periods dry vegetation and soils, making landscapes more susceptible to ignition. Poorly planned landscaping with high-flammability plants near buildings increases wildfire risk during dry conditions.

Extreme Temperature Swings

Colorado is experiencing an increase in extreme heat events and prolonged cold waves. This places significant strain on building comfort systems, resident safety, and housing infrastructure. Rising temperatures and more frequent heat waves drive higher cooling demand and heighten heat-related health risks. Similarly, prolonged winter conditions, including severe cold snaps and snowstorms, increase heating requirements and can tax building insulation and mechanical systems.

Vulnerable Building Systems

-

Thermal Envelope: Poorly insulated and leaky walls, roofs, and windows fail to maintain stable indoor temperatures during extreme temperatures.

-

HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning): HVAC systems not designed for extreme temperature fluctuations struggle to maintain performance, increasing the risk of breakdowns during critical periods. Poorly sealed ductwork contributes to energy loss and comfort issues. Moreover, according to the 2020 Energy Information Administration (EIA) data report, approximately 18 percent of Colorado residents did not have air conditioning as of 2020.

-

Building Materials: Heat degrades asphalt shingles, accelerates siding warping, and stresses expansion joints. Cold causes materials like concrete and steel to contract, leading to structural stress or cracking. Prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures can also cause hydronic pipes not located sufficiently within the thermal envelope to rupture.

Key Challenges

-

Health and Safety: Heat-related illnesses such as dehydration, heat exhaustion, and heatstroke are more prevalent among vulnerable populations, including older adults and low-income families. Poor indoor air quality, exacerbated by heat waves and wildfires, increases respiratory risks. Power outages during cold snaps can compromise heating systems. Hypothermia and frostbite are immediate risks, particularly for under-insulated homes.

-

Auxiliary Heating Systems for Heat Pumps: Cold temperatures in Colorado can drop below the design limits of standard heat pump systems, requiring thoughtful building design to ensure occupant comfort and energy efficiency. To address these challenges, multifamily developments should incorporate appropriate envelope assemblies that enhance insulation and minimize heat loss. Pairing these with cold-climate heat pump technologies specifically designed to perform efficiently in sub-zero temperatures ensures reliable heating even during extreme weather. For the rare periods when temperatures fall below the operational range of heat pumps, integrating auxiliary heating systems, such as electric resistance or natural gas backup, can provide necessary supplemental heat.

-

Ventilation in Cold Conditions: Extremely cold weather presents significant challenges for electric ventilation equipment, as the large temperature differential requires substantial energy to warm outdoor air to comfortable indoor levels.When air temperatures are below operational ranges of heat pumps, heating outdoor ventilation air can require significant electrical resistance backup.